A sign is displayed for Independence Bank in Columbia Falls, Montana. The community lender was founded more than two decades ago and has grown its business by catering to the local population. Its CEO, Dan Bennett, says they should not be involved in recouping the cost of rescuing two failed banks.

Courtesy of Don Bennett

Hide title

Change the title

Courtesy of Don Bennett

A sign is displayed for Independence Bank in Columbia Falls, Montana. The community lender was founded more than two decades ago and has grown its business by catering to the local population. Its CEO, Dan Bennett, says they should not be involved in recouping the cost of rescuing two failed banks.

Courtesy of Don Bennett

Freedom Bank was founded two decades ago in Montana’s Flathead Valley, an area far from Silicon Valley known for fly fishing and whitewater rafting.

The community lender has built its business by catering to local populations, offering a mix of mortgages, car loans and business loans from its home base in the small town of Columbia Falls.

It’s a very different business model than Silicon Valley Bank, which grew aggressively with a focus on tech entrepreneurs. Freedom’s balance sheet is measured in millions, not billions of dollars.

Still, Liberty Bank and other community banks are now worried about helping Silicon Valley and New York-based Signature Bank recover, after regulators last month took the unprecedented step of freezing all deposits at both lenders.

It was a move that helped stabilize the banking sector, but it came with a hefty price tag: $22 billion.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) must now recover that cost. It plans to impose a “special assessment” on banks, but has yet to decide which lenders will have to pay the levy.

Dan Bennett, CEO of Freedom Bank, is adamant that his bank should not get caught.

“I don’t think community banks should pay the price for the disaster,” Bennett argues. Because we have nothing to do with it.

A conservative business model

Bennett started Freedom Bank in 2005 in his basement. Soon, he turned it into a trailer and, later, a large building downtown — not far from the Flathead River.

Independence Bank has grown, but its business model hasn’t changed much. Bennett says the decisions are driven by “common sense.”

“We’re an important part of our community and we’re doing well,” he says. “I like to be safe and fluid.”

Unlike many other lenders, including Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, Freedom Bank is not loaded into U.S. government bonds when interest rates are low. Those investments lost value as interest rates rose, and that was a big reason why those two banks failed.

“We don’t have any losses in our portfolio,” Bennett says.

Don Bennett, founder and CEO of Freedom Bank in Columbia Falls, Montana, stands before his borrower. Bennett founded the bank in his basement and expanded it over the years.

Courtesy of Don Bennett

Hide title

Change the title

Courtesy of Don Bennett

Don Bennett, founder and CEO of Freedom Bank in Columbia Falls, Montana, stands before his borrower. Bennett founded the bank in his basement and expanded it over the years.

Courtesy of Don Bennett

Other smaller lenders resist paying for recovery

Community banks see this as a fundamental issue of fairness.

Under the country’s current system, banks pay into the FDIC’s deposit fund, which insures all deposits up to $250,000.

But when bailing out Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, regulators decided to tap those funds, even though the majority of deposits at both lenders were above that limit and therefore should not have been insured by the FDIC program.

Take the banks of Montana’s Three Rivers, about 20 miles from Columbia Falls in Kalispell.

Community Bank provides the FDIC with more than $130,000 in deposit insurance each year, and CEO A.J.

“For the size of our bank, that’s a huge expense,” he says. “That’s a commercial lender’s salary.”

Like Bennett, King says his bank was run responsibly. It has about $300 million in assets, a strong portfolio of loans to local businesses, including loggers and concessionaires in nearby Glacier National Park.

“We were completely naive about it, and now they’re saying, ‘Okay, banks. You’re going to have to pay for this,'” he says. “I don’t think we should be held responsible for what other banks have done.”

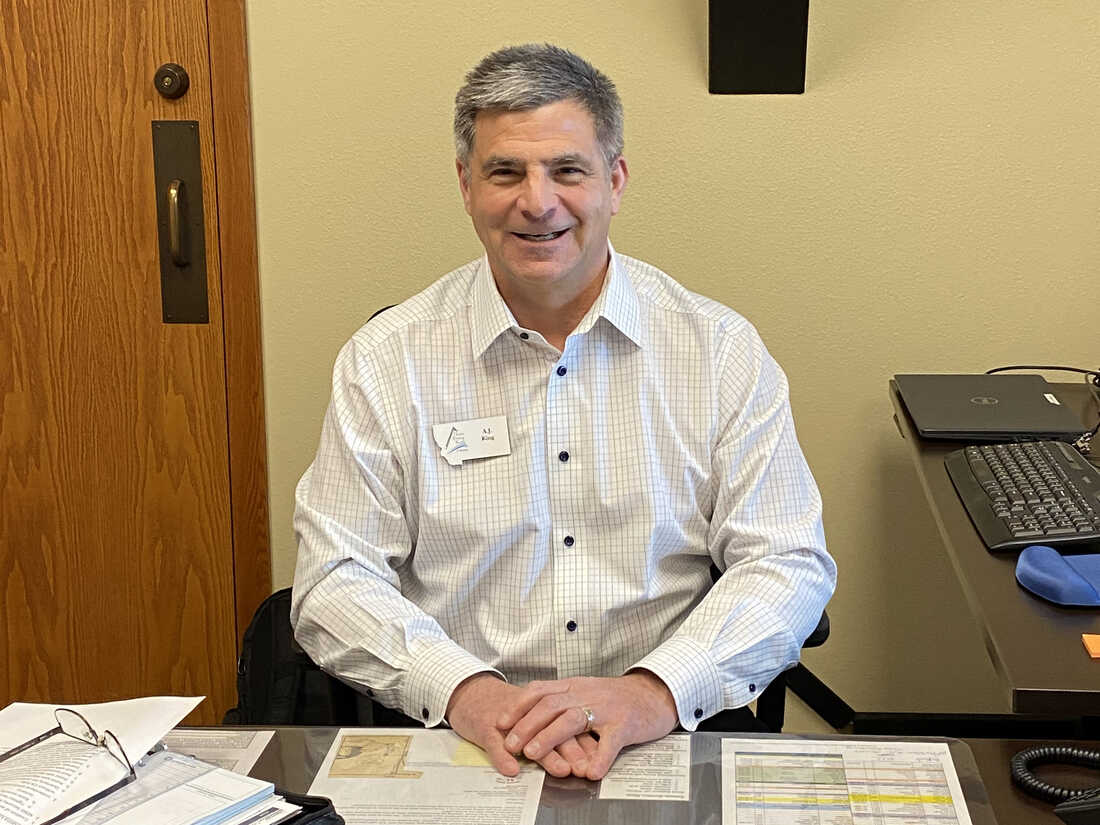

AJ King, CEO of Three Rivers Bank in Kalispell, Montana, sits in his office. King says his bank won’t have to pay for mismanagement at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank.

Courtesy of AJ Raja

Hide title

Change the title

Courtesy of AJ Raja

AJ King, CEO of Three Rivers Bank in Kalispell, Montana, sits in his office. King says his bank won’t have to pay for mismanagement at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank.

Courtesy of AJ Raja

Exemption of Community Banks from any special charges

Lawmakers also say they are hearing complaints from community banks.

Sen., a Republican from Montana, where both Freedom Bank and Three Rivers Bank are located. Steve Daines voiced his concerns at a recent Senate hearing with top regulators, including FDIC Chairman Martin Grunberg.

“We’re facing a situation where responsible banks in my home state of Montana and elsewhere are going to have to bail out irresponsible, offshore banks with billions of dollars more,” Daines said. .

Grunberg didn’t make a firm commitment, but he sympathized.

“We’re going to be very sensitive to the impact on community banks without predicting what our board is going to vote,” the FDIC chairman told lawmakers.

The White House has said it supports exemptions for small, community banks, though that will ultimately be a decision for the FDIC to make. The regulator said it would publish its proposal for a special assessment in May.

More restrictions may come

Even if the FDIC decides to exempt community banks from paying fees, smaller lenders like Independence Bank and Three Rivers Bank could suffer long-term damage from last month’s banking crisis.

Many smaller banks have seen customers move money to larger lenders and are bracing for increased regulation of their businesses.

For example, the Federal Reserve is considering increasing the number of banks that undergo stress tests, although it would exempt smaller lenders.

Meanwhile, the White House has asked Congress to give regulators the power to claw back compensation from executives at banks that fail because of “mismanagement and excessive risk-taking.”

A flock of sandhill cranes flying in Kalispell, Montana on the banks of Three Rivers in Montana.

Avalon/Universal Images Group via Getty

Hide title

Change the title

Avalon/Universal Images Group via Getty

A flock of sandhill cranes flying in Kalispell, Montana on the banks of Three Rivers in Montana.

Avalon/Universal Images Group via Getty

Three Rivers Bank has more than 50 employees, many of whom were hired solely to comply with the current rules, King says.

“Half of them never talk to a customer,” he says. “It’s all because of regulation.”

King has been a banker for 37 years now, and he says it’s not as fun as it used to be.

Now, with events hundreds of miles away, he worries it will become even less fun.

“I’ll tell you,” he says. “It’s very difficult to be a small, independent community bank these days.”